Much is said about the issues and challenges of planning for large scale housing growth, the difficulties of our current planning system, and what might need to happen to enable worthy projects to proceed.

First off, let’s start on a positive note. Developments at scale have got through the present system. Just look at Gilston in East Herts, Northstowe and Waterbeach in South Cambs, Welborne in Fareham and many others. These have all passed scrutiny, are in adopted Local Plans and have proceeded to live planning applications. They are real and will happen. But all is not positive, with a series of more recent initiatives hitting the buffers.

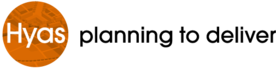

North Essex is one of the more recent cases which has attracted attention. For those not following things that closely, the ‘North Essex Authorities’ (NEAs) of Braintree, Colchester and Tendring had set out a shared approach in their respective Local Plans that were collectively submitted to the Planning Inspectorate for examination. As well as policies on housing, employment and infrastructure, 3 cross-boundary Garden Communities were also proposed. These were large standalone places containing residential, employment, social infrastructure, new accessible open space and were to be delivered to ‘Garden City’ principles.

North Essex is one of the more recent cases which has attracted attention. For those not following things that closely, the ‘North Essex Authorities’ (NEAs) of Braintree, Colchester and Tendring had set out a shared approach in their respective Local Plans that were collectively submitted to the Planning Inspectorate for examination. As well as policies on housing, employment and infrastructure, 3 cross-boundary Garden Communities were also proposed. These were large standalone places containing residential, employment, social infrastructure, new accessible open space and were to be delivered to ‘Garden City’ principles.

The initiative was the largest in the Governments Garden Communities programme and was considering and testing new delivery and funding mechanisms. 2 successful HIF awards had been made providing nearly £400m to support the delivery of strategic infrastructure. A delivery company was established, with recognition that it could have become one of the first greenfield ‘Locally Led New Town Development Corporations’.

The North Essex proposals were significant, transformational and controversial. Parts of the local communities affected did not want this scale of development in their neighbourhoods and a well organised local campaign group put considerable time and effort into challenging the proposals.

Proposals of this nature are big, costly, and ambitious. In the North Essex case they were backed by extensive evidence – much more than normally seen at a Local Plan examination – but inevitably involved assumptions and uncertainties. After a few sets of Hearing Sessions, the Inspector set out his views and concluded that 2 of the proposed Garden Communities were in his opinion undeliverable.

The outcome was a blow for the Councils concerned. Whilst they continue to take forward the plans with modifications to address the Inspector’s concerns, it is not the same ambitious and forward thinking initiative they started out with.

Isn’t this all too difficult?

The North Essex outcome, and the way that ‘soundness’ was tested does make things very difficult for anyone contemplating similar planning for the long term such as for new settlements, Garden Communities or strategic growth. Uncertainties will always exist over future market conditions, how people will live their lives, what funding opportunities may exist, etc. We all know this too well by the rapid change the recent pandemic has forced upon us all.

Many across the planning profession (myself included) are in it because we want to deliver beautiful and successful future development, and see that by doing it at scale there is the ability to create better places with the proper infrastructure, design and placemaking objectives built in from the outset. There is far too much piecemeal and monotonous urban sprawl that builds up over decades in a rather haphazard and unsatisfactory way. Local politics and short term thinking tends to prevail to the detriment of long term leadership and vision.

The proposals in North Essex suffered from a comparison to this recent history yet were actually proposing something much different. The arguments were made that the ambitions would not be realised. The evidence-based process ended up giving higher weight to examples from the recent past than an appreciation of what we may want for the future.

North Essex Section 1 Local Plan Examination in Public

A more pragmatic approach to deliverability

The North Essex outcome primarily revolved around the consideration of ‘deliverability’.

The Examination was led into a detailed review of facts, figures, timings, assumptions and opinion. There were viability assessments produced by multiple parties. Every assumption was heavily scrutinised. Financially astute participants at the Examination knew what would make such schemes sink or swim.

Detailed and uncertain assumptions like contingency allowances came to the fore. The Inspector made his judgement based upon only one of the scenarios presented with the highest contingency allowance of 40% even though this is an extra buffer for risk and not a defined fixed cost.

Inflation based scenarios were also presented based upon a more cautious view of future price growth than evidence based historic trends. For long term projects inflation will occur, but it will never be possible to be definitive on the detail. The Inspector considered the inflation scenarios to be unreliable.

In terms of the deliverability of long-term strategic infrastructure, the Inspector considered that certain suggested routes for a proposed Rapid Transit System were undeliverable. Initial feasibility work had been undertaken which set out a range of potential route options, with some connections not needed until 2034 at the earliest. At this stage in the process it was not possible or proportionate to expect confirmation of funding or more detail.

North Essex proposed ‘Rapid Transit System’

North Essex was being judged against the 2012 NPPF and there have been changes with a better recognition of long term uncertainty. Paragraph 72 provides support for planning at large scale and sets out a range of important considerations. The addition of footnote 35 is an attempt to acknowledge long term infrastructure uncertainty. But would the outcome have been different if the current guidance was being applied? To my mind it doesn’t introduce anything revolutionary and pragmatism ought remain constant.

Longer term strategic projects will always involve delivering infrastructure many years into the future. New funding initiatives evolve all the time, either to promote and support certain policy ambitions or to address specific funding challenges as they emerge. For large housing sites there have been a plethora of initiatives over the past decade. We also know that investment in infrastructure and its contribution to national and local economic prosperity is well understood, and will always be prominent in future Government thinking. That in itself should bring confidence that there would be a reasonable prospect for future funding support for infrastructure should it be required.

The benchmark land value conundrum

The limitations of the viability assessment process came into sharp focus. The Inspector in North Essex heard much on the level of land value expectations in the market but was provided with no real relevant or tangible evidence to justify them. He ultimately ruled out 2 of the 3 Garden Communities because he didn’t think they would provide sufficient incentive to landowners, despite the promoters of all the sites being present at the Examination and supporting the deliverability of their land.

Various promoters approached the examination in a fairly standard way with a general expected minimum requirement of £100,000 per gross acre when it is only presently worth circa £10-15,000 per acre as farmland. Viability models were prepared by a number of consultancies which sought to demonstrate the uplift was achievable. The Inspector dismissed much of what was presented to him by the promoters. The NEAs approach set out what land value could be achieved after delivering infrastructure and policy requirements.

The Inspector concluded that a range of £50,000-£100,000 would in his opinion be necessary to meet the ‘competitive return’ test. Only one of the Garden Communities got sufficiently over this bar. Another was considered too marginal, at £52,000 per acre – albeit based on a scenario of a lower build out rate, no inflation, no infrastructure grant funding support and maximum (40%) contingencies added. The other scheme in his opinion fell too far short, although residuals even with the highest contingencies were always a multiple of EUV.

This experience should act as a wakeup call to all landowners and anyone involved in advising them on what to expect in terms of benchmark land values. Prices paid, assumptions applied elsewhere on incomparable schemes are irrelevant, as are the fag packet or rule of thumb figures which often get bandied about. The lazy approach to quote simple but inappropriate numbers has to stop.

The updated PPG  is now clear on the need for land value expectations to incorporate infrastructure and policy considerations. All must properly follow planning guidance. What this generates is the return you can expect.

is now clear on the need for land value expectations to incorporate infrastructure and policy considerations. All must properly follow planning guidance. What this generates is the return you can expect.

Simple logic would dictate that if this was higher than the asset was currently worth then that is a positive thing worth doing. It is however never quite so simple. Further acknowledgement is needed that this may be a life changing decision, the uplift needs to be meaningful and that in the absence of any compulsion, landowners may decide to sit tight.

These types of issues cannot be easily accommodated through a generalised approach to viability. If the ‘premium’ cannot be sufficiently defined then surely we need a simpler test – how about a simple comparison to EUV, an acceptable defined multiple, or % extra as a premium. This together with a more positive approach to intervene where landowners sit back and demand returns that hinder delivery, could get us over these perennial problems.

Supporting positive, forward looking Councils

It has undoubtedly been a painful and costly experience process for the North Essex Authorities. The immediate response from MHCLG was encouraging in that the Ministry recognised the ambitious approach that was being taken. These kinds of projects require many years of positive, proactive and detailed work at a local level to put in place the required strong foundations.

We all know the resource and capacity issues faced by local Government. In that respect initiatives such as the Planning Delivery Fund and Garden Communities programme have been invaluable to many places. Let’s hope such support continues and is expanded into the future.

There is also a broader point around public sector leadership, which underpins most of the key aspects – safeguarding the delivery of quality, providing long term patient funding, and ensuring there is a positive approach to community development and stewardship. In this regard there is a model to look back on and which may well provide a more all-embracing solution – deploying the powers to establish ‘locally led’ Development Corporations to coordinate the placemaking and delivery process. Pre COVID 19 the March Budget stated the intent to set up such bodies in the Ox Cams corridor.

We can now see how Government is thinking about the future as per the proposed reforms set out in the White Paper. We’ll set out some thoughts on this in a future ‘Views’ piece, but suffice to say the approach to long term strategic proposals such as new settlements don’t appear that well addressed by the new ideas.

There is definitely a need to find a way to effectively navigate the planning system, avoid past mistakes and ensure new approaches can actually make a real difference. But maybe we already have the tools and simpler changes could provide the best chance for speedier implementation and impact, rather than some of the major proposals that have been put on the table.

The views expressed are personal reflections from Rob Smith, Director at Hyas Associates who attended the Examination hearings on behalf of the North Essex Authorities.