Our l ast ‘Views’ piece considered the challenges that large residential schemes faced in progressing through the current planning system, using North Essex as a case study. Now that the Planning White Paper is in front of us, it is worth considering whether the proposals provide an appropriate basis to deliver the improvements that are needed.

ast ‘Views’ piece considered the challenges that large residential schemes faced in progressing through the current planning system, using North Essex as a case study. Now that the Planning White Paper is in front of us, it is worth considering whether the proposals provide an appropriate basis to deliver the improvements that are needed.

Of course, it’s hard to evaluate whether all of the ‘big ideas’ will be beneficial without knowing more of the important detail on how things would be implemented. However, it doesn’t look great in terms of planning for long-term strategic growth, and without greater care and thought the proposals risk taking things backwards.

We have included a copy of our response to the consultation at the foot of this Blog, which expands upon many of the points set out below.

New Local Plans & Proposed Growth Areas

This is a key part of the reforms and where the issue of strategic growth needs very careful consideration. There are several particular concerns.

Timescales. There is no real incentive to plan strategically for the long term and commit to greater growth beyond the plan period. This is an issue now under the current system, and the planning reform provides an opportunity to do something about it. However, very little is said in the White Paper to support such ambitions. The only reference to the potential timescale of the new Local Plans is referred to as “a minimum of 10 years”. Without specific encouragement for longer term planning, the focus will inevitably be on meeting the housing requirements for that time period.

The current planning system does little to support places that have vision and want to make long term spatial decisions for their areas. Too often, places get fixated on the do minimum. leading to a piecemeal approach to growth and ineffective planning for infrastructure.

If we want to deliver many of the objectives of the White Paper, shouldn’t Councils be being encouraged to think about longer term requirements? This may need a distinction between getting a more detailed and expedient system for short/medium term proposals, but a more flexible approach for longer term strategic growth, ideally across boundaries.

Some incentive ought to be on the table for those places which are willing to make longer term commitments. This could be done by acknowledging that the standard method to assess the distribution of the national housebuilding target would also have regard to housing already committed to by a Council beyond the standard Local Plan period.

The very largest proposals such as for new settlements could potentially be considered through an alternative approach, possibly via some other form of larger than local statutory plan policy basis which can better consider the scale of growth together with investment in cross boundary strategic infrastructure.

Strategic Cooperation. The White Paper states that the Duty to Cooperate test would be removed but sets out no replacement. Moves are already underway for Government to lead with some form of statutory “larger than local” planning for the OxCam corridor. There had been anticipation that a forthcoming devolution and local recovery white paper may help to address the gap, albeit it appears that is now being pushed back to 2021. In any event such an important aspect should surely be picked up within the scope of such major planning reform proposals. Strategic growth will inevitably require cooperation and collaboration across boundaries, with the larger sites relating closely to neighbouring areas and having relationships to wider market considerations and strategic infrastructure. Again, without any incentives or requirements to secure positive cooperation between neighbouring authorities will places be put off from thinking strategically about future growth?

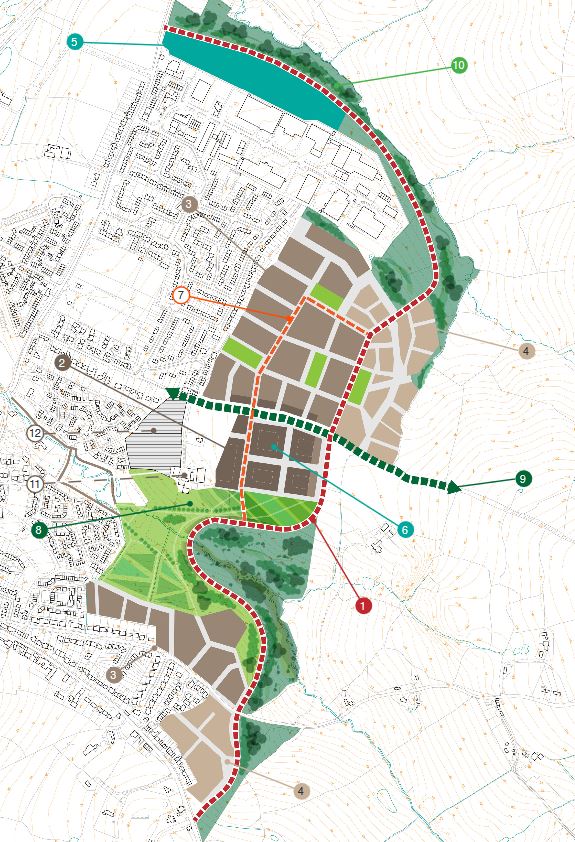

Growth Areas. There will need to be clarity around what entails “substantial development” to be included within the Growth Area category, but it is reasonably clear this is where major urban extensions and new settlements would sit.

Growth Areas. There will need to be clarity around what entails “substantial development” to be included within the Growth Area category, but it is reasonably clear this is where major urban extensions and new settlements would sit.

The approach to be taken to Local Plans appears to be heavily driven by the ambition to streamline the consenting regime. A ‘Growth area’ category would better relate to proposals that are intended to be delivered in the early years of the plan period and in full (or substantially) within its lifetime. These would benefit most from some form of permission as the plan is adopted. It is however not suited to the needs of longer-term strategic growth, which could span several plan periods and requires flexibility to adjust to influences over time.

A different category (‘Strategic Growth’) could be introduced for the largest, more strategic and complex sites which deliver later on in and/or beyond the end of a plan period. More flexibility could be introduced for these proposals not to require the same level of detail or background information. Such a distinction could avoid any unintended consequence of pushing Councils away from planning strategically beyond plan periods. It would also help to address concerns over the amount of work that may need to be undertaken for the largest most complex sites, the related resourcing requirements the risks this puts on achieving the ambitious plan making timescales.

Alternatively, Strategic Growth could be addressed through an altogether different form of plan making at a larger than local scale.

‘Best in Class’ Public Engagement. The overall approach puts considerable extra pressure on front-loading of engagement and participation. It feels like the reforms are being too ambitious in shoehorning the larger and most controversial proposals into a standardised and time bound process. Communities may well feel let down that big projects get rushed through the system not allowing for appropriate engagement. Promoters themselves may feel it is rushing a process that works better through a staged process of building up the detail and de-risking.

Automatic Consent. The objective is clear – to avoid the need for multiple stages which reopen matters which ought to have already been sorted. The general approach appears to merge the site allocation process in a local plan with a planning approval stage in development management. Within growth areas the reference to LDOs and DCOs seems to recognise that for some proposals the Local Plan will only ever get you so far.

LDOs have been with us for some time, with very little take up for larger mixed use or residential led schemes. There are reasons for this, which ought to be understood when thinking about proposing the approach for wider application. A key aspect is the resources required for a Council to effectively take the lead in preparing material similar to an outline planning application, and the need for such proposals to be adequately market facing to enable others to then deliver on them. There are other matters to sort out in terms of the delivery of site specific infrastructure.

The potential of the DCO route for larger scale residential schemes is not new. The clarity of process, timescale and decision making are undoubted attractions. The question will be whether it can be suitably flexed to take account of requirements over potentially long time periods. Doing a DCO for a new settlement/urban extension will be very different to doing one for a motorway junction or power station where the engineering proposals will be better defined and much less subject to ongoing variation in design, character and beauty. It seems sensible to include it as an option for large scale residential schemes, but the process will no doubt require some adjustment. It will then need to be tested.

The alternative approach to recognise some form of ‘Strategic Growth’ category could make a clearer distinction over what the Local Plan is providing by way of approval. It is likely to come back to aspects such as the type and quantum of development, key design principles and infrastructure/policy requirements. This sounds very similar to a well worded site allocation policy.

Background Evidence & the Proposed Sustainable Development Test. A key issue from the North Essex case was the high expectation that was set on deliverability as part of the test of soundness. In that respect an overhaul to a single statutory “sustainable development” test could (if appropriately defined) provide a more proportionate and pragmatic approach. Care will be needed to ensure there is clarity and guidance around any new definition and its application to minimise the risk of inconsistency. It should also only be introduced with associated tightening up to achieve more beautiful development with the right infrastructure.

A simplified checklist of background evidence studies would also be helpful to address wasted effort, resources and debate. A clamour for detail will simply not be possible when talking about schemes which may take 10, 20 years or longer to deliver. Costly, voluminous documents like Sustainability Appraisals do little to help local communities evaluate proposals, and only really serve to feed the debate between those who either do or don’t want something to happen.

The current NPPF and PPG already provide a clearer position on aspects of this (such as a greater recognition of infrastructure uncertainties). Much of what is intended could be achieved by further changes to policy & guidance.

Beauty

There is little to argue against a desire to promote better design and placemaking. It remains to be seen how beauty is to be defined and agreed nationally and locally.

There is little to argue against a desire to promote better design and placemaking. It remains to be seen how beauty is to be defined and agreed nationally and locally.

A new expert body is proposed and has been initiated by the Ministry. Some care will be needed to deploy this expertise so that it can fit in to current structures and practice to support and enable local ambitions. It should not be some distant and centralised entity that is imposed from above or that takes resources and power away from where needed at a local level.

The proposal for some form of “fast tracking” may have some potential, but it will need Councils to be able to take a lead and make sure any masterplanning or design coding is done to the highest standards. This will need a careful approach to governance especially where a reliance is being placed on the site promoters to take on and fund the preparation of necessary material.

Infrastructure & Delivery

A consolidated Infrastructure Levy. The White Paper states upfront that securing contributions and capturing more land value uplift to deliver new infrastructure is “central to our vision for renewal of the planning system”. It says little about how the value of any new charge/levy would be set. It is therefore impossible to consider whether it would achieve the objective. There are many questions related to this. Of particular significance would be what allowance is being included for the returns to landowners and developers, and for the larger sites how will their substantial infrastructure needs be properly accounted for.

It is difficult to understand how, in practice, “enabling borrowing combined with a shift to levying developer contributions on completion, would incentivise local authorities to deliver enabling infrastructure”. The larger sites will involve the provision of costly strategic infrastructure which will be required at early stages in the development process. The suggested amendments pass the responsibility and funding risk over to Councils who would be expected to forward fund necessary infrastructure, by taking on debt but without control over payback. Whilst there may be contractual solutions to overcome issues (such as fixed sequences of payments, long stop dates, etc) it is difficult to imagine the majority of Councils being willing or able to take on such major financial risks and responsibilities. The devolution and local recovery white paper will be relevant as bigger combined authorities may be part of the solution, but its proposals are yet unknown. Alternatively, Homes England are already delivering a range of infrastructure investment programmes and could be well placed to act as a national ‘banker’, spreading risk and delivering a dedicated national investment programme.

The proposal to provide freedom on spending of any levy risks severing a link between this being directly related to infrastructure, or just a form of tax/revenue generation for general purposes. Reference is made to this flexibility being appropriate “once core infrastructure obligations have been met”. Clarity is needed as to how this will be defined and safeguarded.

It is impossible to comment on the attractiveness of a new system without further information. It may be an area where some form of standardised and simplified levy approach could apply to certain types and scales of development, but it does not seem appropriate for larger, infrastructure intensive proposals. For these the traditional S106 mechanism is likely to provide greater clarity and certainty to all parties on what is required and when, and to perform a key role of S106 in making developments or their impacts acceptable. Negotiations could be improved by clearer guidance, to strengthen the PPG with respect to standardised considerations on viability, including dealing head-on and defining an appropriate ‘premium’ when considering land value thresholds.

Supporting innovation in delivery. The White Paper says very little on delivery vehicles. This is particularly important as the reforms are increasing pressure on the public sector to streamline the process yet provides them with no tangible tools to intervene should it be necessary to ensure that the private sector then delivers. The same intent was behind previous reform in 2012 and it did not lead to a step-change in housing supply. As a minimum, Development Corporations with suitable planning and delivery powers, including the ability to acquire land at no-scheme world values, and backed by access to sufficient revenue funding to help local partners implement and run them, should be made available for those wishing to play a more active role. Equal pressure should also be put on developers to deliver on the sites they put forward.

People & Skills

The proposals will have a profound impact on planning resources and skills. If the Government is serious about the reform delivering results, then it will need to show how the service will be funded and delivered. There is reference to the cost of operating the new planning system being principally funded by landowners and developers. It is not made overly clear how, but it appears that the Levy may be used to achieve this with reference to a proportion earmarked to cover planning costs. In the absence of any information on the scale of any Levy or the funding it is not possible to judge if this is a suitable proposal. It would however further dilute the ability and purpose of the Levy to fund necessary infrastructure. The timings are also out, as there will be a need for higher upfront funding for plan making with Levy receipts spread out into the future.

The proposals will have a profound impact on planning resources and skills. If the Government is serious about the reform delivering results, then it will need to show how the service will be funded and delivered. There is reference to the cost of operating the new planning system being principally funded by landowners and developers. It is not made overly clear how, but it appears that the Levy may be used to achieve this with reference to a proportion earmarked to cover planning costs. In the absence of any information on the scale of any Levy or the funding it is not possible to judge if this is a suitable proposal. It would however further dilute the ability and purpose of the Levy to fund necessary infrastructure. The timings are also out, as there will be a need for higher upfront funding for plan making with Levy receipts spread out into the future.

Adequate resourcing of Council planning functions will underpin any chance of reforms being implemented effectively. A commitment to funding support local planning authorities to transition to the new planning system as part of the next Spending Review is welcome, but it will not just be a time-limited need. The recent RTPI submission to the Spending Review illustrates the strength of feeling, with circa £500m suggested as being needed. Its highly doubtful such funding will be possible, but there will need to be serious commitment to help Councils deliver on their new responsibilities and give the reforms any chance of success.

Response to the Consultation

Click here to download a copy of our response to the Planning White Paper. This expands upon many of the points raised above. If you agree with any of the points being made, feel free to copy and use any elements as part of your submissions.